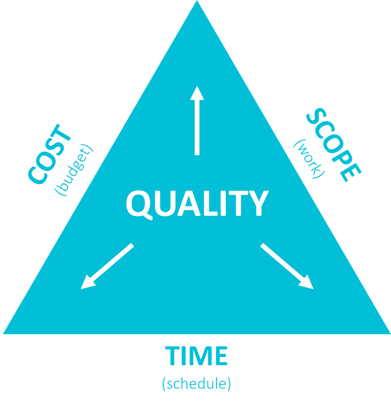

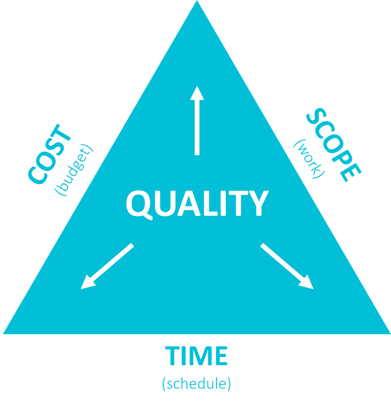

One of the basic premises of project management lies in understanding the triple constraint. In summary, all projects are constrained by 1) Time (e.g., the schedule), 2) Cost (e.g., the budget), and Scope (e.g., the work). Think of a simple triangle (depicted below), with each constraint representing a side. Move one side, and the other side(s) will be impacted. For example, if project scope is increased—then there’s impact to cost and/or time. A fourth dimension (quality) lies in the middle of the triangle and is a collective reflection of the three constraints. For example, reducing the schedule with a static scope and cost will likely impact quality of work delivered.

Very basic theory, but as a project manager, I often find myself having to remind and defend this principle. Overly optimistic project participants, senior sponsors pressured to deliver more for less, and eager end users wanting new and enhanced functionality all contribute to subliminal denials of this project management tenet.

Common Scenarios

- Scope creep—a slow pace of seemingly small items gets added to project scope, with the belief of no impact to a set delivery date. What typically happens is either quality of work is impacted (e.g., think "tactical" or "work-around" solutions), or scheduled delivery dates get pushed back.

- Resource constraints—oftentimes the project team is understaffed from the start, or project resources over time get diverted to other "higher priority" efforts or supporting BAU. The drawback on resources then impacts the work, which leads to schedule delays or quality concerns.

- Time-boxed delivery dates—how many times are we given client/regulatory/business driven delivery dates, and then asked to complete necessary work with a set budget?

- Rework/productivity—there are a lot of things I can put in this category—from undertaking thorough requirements definition to proper testing to staffing projects with the right resources. If not done right, all can quickly drain productivity and lead to higher levels of rework.

- Larger initiatives—over greater periods of time, these projects can provide a false sense of security that “we can make it up” or “we’ll work hard towards the end and get it done.” Small change items occurring across project workstreams are typically not felt until later stages when everything starts coming together (e.g., "end-to-end" business process validation).

What can we do to ensure implications of the triple constraint remain front and center to key project stakeholders? First, project managers must be diligent to recognize and document any time/cost/scope impacts, no matter how small. And once an agreed threshold is reached, there should be a realistic re-plan or trade-off to bring the triple constraint back in line. As an example, if we have approved change controls to add an additional 120 hours of work then we need to either de-scope other work, add resource bandwidth, or adjust the timeline. Simply thinking the impact will be somehow absorbed without consequence is ill-informed thinking.

Additionally, prior to a formal project kick-off, we must undertake thorough planning to ensure our baseline scope estimates are accurate, project resources are adequate, and our timeline is reflective of realistic milestones. Adding some project buffer will help soften the typical constraint challenges likely to occur. But if the overall plan is flawed from the start, then it becomes difficult to manage changes going forward. Shortchanging the project estimation process is akin to building a home on a shaky foundation.

In summary, the triple constraint is a simple, but useful tool to help temper project expectations and provide a framework for communicating with key stakeholders. Once the concept is understood, protocols can then be agreed and established to cover change control, resourcing, and re-planning. There are certainly other methods beyond the triple constraint to help guide the future path of a project (e.g., opportunity cost/benefit analysis). However, level setting changes to time, cost, and scope should be reviewed with the triple constraint theory in mind. The next time someone asks you to deliver a project quickly, cheap, and of high quality—remind them that “something’s gotta give.”

Comments