Are you part of the generation who remembers the time when the investment desk and operations were a few metres or one floor away, where daily interactions led to professional relationships and exchange of knowledge? Or are you part of a newer, siloed generation where understanding the up and downstream investment processes has been more difficult to navigate? By segmenting our organizations into areas of specialized knowledge, how many inefficiencies have we propagated over time? Are we also increasing business and operational risks where thoughts and actions in one location could unwittingly impact another location?

To overcome the challenges and complexities of the modern investment management organization, we believe that experts at every point of the investment lifecycle need to continually learn and develop. How much time have we spent in the last year—even 18 months—reflecting on the knowledge and skills that has been obtained versus the knowledge and skills we will need in the years ahead. How many appraisals have a learning objective stated, but the objective has not been met, been left for another year?

Many believe it is incumbent on us all, not just line management, to seek out learning opportunities to help us develop personally, professionally, and within our wider teams. We need to remove any stigma that we do not have to continually improve and learn. Are we able to say “we don’t know that process, how does that work? What are the consequences if this process fails?” or we are too experienced or too busy to learn as our careers develop?

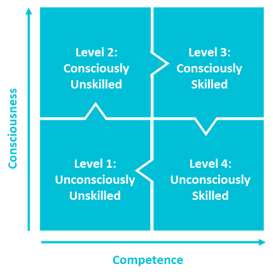

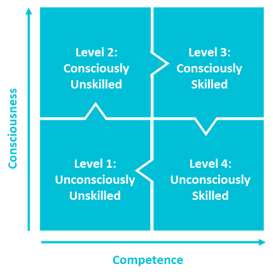

We believe success is achieved by following the four-stage learning cycle to take us all from unconscious incompetence, working through conscious incompetence and conscious competence to finally achieve unconscious competency. If you’re unfamiliar with this framework, this diagram helps illustrate the point. The premise of this learning cycle idea is that we all enter a new role as unskilled and unaware of exactly what our skill gap is. As we move through the process of learning, we identify that gap, and then begin putting new skills into practice. Once these skills have been sufficiently practiced, we’ve achieved a level of expertise where a skill becomes second nature and can be done almost unconsciously—depicted as level 4.

We believe success is achieved by following the four-stage learning cycle to take us all from unconscious incompetence, working through conscious incompetence and conscious competence to finally achieve unconscious competency. If you’re unfamiliar with this framework, this diagram helps illustrate the point. The premise of this learning cycle idea is that we all enter a new role as unskilled and unaware of exactly what our skill gap is. As we move through the process of learning, we identify that gap, and then begin putting new skills into practice. Once these skills have been sufficiently practiced, we’ve achieved a level of expertise where a skill becomes second nature and can be done almost unconsciously—depicted as level 4.

An organizational example of this came to light when working on a target operating model review at a large, global investment management company. When reviewing the corporate action processes and the interaction between portfolio managers and operations, a subtle difference of understanding in response time surfaced. The portfolio managers thought they had more time to make their corporate action decisions, but were not aware that after instruction, operations needed to consider another set of custodian deadlines to ensure the actual corporate action decision was processed in the market. The teams worked in separate buildings and it wasn’t until they’d had a number of discussions about concerns of missing a deadline that both teams identified the knowledge gap.

By seeking a better understanding of the underlying processes and assumptions, both teams elevated their unconscious knowledge gap to a conscious one. The portfolio manager became more aware of the downstream process and the operations team became more aware of the challenges and timing issues the portfolio managers have to consider in their decisions. Though neither team needed to become experts in the others’ function, an understanding of skills gap and proactive education broke down barriers that were potentially creating operational risk for the firm.

This example is just one of many that highlights the increasing necessity of proactive knowledge acquisition. For continued professional success, it is more important than ever to take the time to self-invest and complete a professional knowledge and skills gap analysis. Think of an upskilling objective, aim to achieve it in 2021, and set yourself up for more success in the years to come.

We believe success is achieved by following the four-stage learning cycle to take us all from unconscious incompetence, working through conscious incompetence and conscious competence to finally achieve unconscious competency. If you’re unfamiliar with this framework, this diagram helps illustrate the point. The premise of this learning cycle idea is that we all enter a new role as unskilled and unaware of exactly what our skill gap is. As we move through the process of learning, we identify that gap, and then begin putting new skills into practice. Once these skills have been sufficiently practiced, we’ve achieved a level of expertise where a skill becomes second nature and can be done almost unconsciously—depicted as level 4.

We believe success is achieved by following the four-stage learning cycle to take us all from unconscious incompetence, working through conscious incompetence and conscious competence to finally achieve unconscious competency. If you’re unfamiliar with this framework, this diagram helps illustrate the point. The premise of this learning cycle idea is that we all enter a new role as unskilled and unaware of exactly what our skill gap is. As we move through the process of learning, we identify that gap, and then begin putting new skills into practice. Once these skills have been sufficiently practiced, we’ve achieved a level of expertise where a skill becomes second nature and can be done almost unconsciously—depicted as level 4.

Comments